Lele Buonerba is a graphic designer with extensive experience working in contemporary art galleries and institutions in Milan, Chicago, and New York.

Journal

Sound Art and Music: Drawing an Invisible Line

February 2018 • File under: Contemporary Art

Sound art and experimental music may seem, at first glance, quite similar disciplines. In certain ways they are; they share many of the same composition, production and performance tools. As many contemporary artists embrace interdisciplinary practices, and as a number of musicians show interest in and may even produce visual art, there continues to be a growing amount of artists working across both mediums of art and music. It can be difficult to understand exactly what falls under sound art, and what may simply be music performed or played in a contemporary art venue. By analyzing the works’ aesthetic values, rather than by comparing the often very similar processes and outputs, we can attempt to distinguish sound art from music.

To explore the relationship between music and sound art we look to contemporary examples of figures working between the two worlds. Today many experimental musicians are invited to play concerts, club nights, and even performances hosted at contemporary art venues; some have even been asked by curators to make soundtracks for an exhibition. In 2016, on the occasion of the 16th Quadriennale di Roma, Italian electronic music producer Lorenzo Senni created, under his moniker Stargate, a soundscape inspired by the city of Tokyo for the exhibition curated by Luca Lo Pinto, A occhi chiusi, gli occhi son staordinarimente aperti. In these kinds of situations it is particularly difficult to distinguish between experimental music and sound art. When music enters a contemporary art institution, does it become sound art?

Laurie Anderson

Drawing of Laurie Anderson’s tape-bow violin

Based in New York, Anderson was at the forefront of experimentation in both art and music, and would often combine the two in her performances, such as in the notorious Duets on Ice, in which she would play a violin alongside a recording while wearing ice skates with the blades frozen into a block of ice. Each performance of Duets on Ice would last as long as it took for the ice to melt. While the music she played at multidisciplinary venues such as The Kitchen didn’t constitute as sound art on its own, the act of performing against a tape recording and playing until a block of ice melts certainly fits the performance-based sound art bill. The tape player fills the role of co-performer while the ice acts as somewhat of a conductor, defining the duration of the piece.

Not all of Anderson’s artistic endeavors are based on performances, or rather on her own performing. In 1978 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York she exhibited Handphone Table, an installation in which two viewers must sit down and press their hands against their heads while their elbows are connected to certain spots of the table. By doing so, the listeners can hear the playing of recorded music in their heads.

Laurie Anderson, Handphone Table, 1978

Wooden table, amplifiers, electronic equipment, two wooden chairs, photograph

Photo: Blaise Adilon

Wooden table, amplifiers, electronic equipment, two wooden chairs, photograph

Photo: Blaise Adilon

Janet Cardiff

Canadian artist Janet Cardiff (1957– ) creates sound installations; often together with her musician husband George Bures Miller. She is known for a series she started in 1991 of site-specific walks. These walks are comprised of recordings which listeners experience by walking through a certain environment while wearing headphones.

Janet Cardiff, Wanås Walk, 1998

Photo: Anders Norrsell

In her own introduction to the audio walks, Cardiff says:

The format of the audio walks is similar to that of an audioguide. You are given a CD player or iPod and told to stand or sit in a particular spot and press play. On the CD you hear my voice giving directions, like “turn left here” or “go through this gateway,” layered on a background of sounds: the sound of my footsteps, traffic, birds, and miscellaneous sound effects that have been pre-recorded on the same site as they are being heard. This is the important part of the recording. The virtual recorded soundscape has to mimic the real physical one in order to create a new world as a seamless combination of the two. My voice gives directions but also relates thoughts and narrative elements, which instills in the listener a desire to continue and finish the walk.

By employing binaural audio recordings (used to achieve 3D stereo sound) and layering multiple tracks – sound effects, music, and voices – Cardiff is able to create a lifelike reproduction of sound. Music producers also use the same techniques, and some experimental musicians might also layer voices and field recordings in a similar way. But their productions don’t classify as sound art since they don’t directly relate to the environment that surrounds the listener.

Janet Cardiff, The Forty Part Motet, 2001

Reworking of “Spem in Alium Nunquam habui” (1575) by Thomas Tallis; 40-track sound recording (14:00 minutes), 40 speakers

Reworking of “Spem in Alium Nunquam habui” (1575) by Thomas Tallis; 40-track sound recording (14:00 minutes), 40 speakers

Installation view at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, 2012

Photo: Colin Davison

Photo: Colin Davison

One of Cardiff’s most renowned installations, The Forty Part Motet, is a fourteen-minute loop of English composer Thomas Tallis’s sixteenth-century composition Spem in Alium, sung by the Salisbury Cathedral Choir, and recorded in individual channels for each singer. Each channel is then reproduced on one of the 40 speakers that make up the installation. This allows the audience to move about the room and listen to the recordings coming from each choir member’s individual microphone. Included is also three minutes of intermission, in which people’s chatter, coughs and other sounds are played across the room. By giving the audience the opportunity to hear certain isolated channels and allowing them to walk around the installation – altering their experience with every step – they become listeners, performers and composers at once.

William Basinski

While Janet Cardiff is arguably not a musician, American composer William Basinski (1958– ) is arguably not a sound artist. He’s a classically trained clarinetist that studied jazz composition, and his work is influenced by that of minimalist composers such as Steve Reich. During most of his lifetime, while living in New York, he experimented with reel-to-reel tape recording and manipulation. His most famous work, The Disintegration Loops (2002–2003), was recorded from a series of ambient music tapes he had made twenty years prior that gradually deteriorated each time they were looped. The creation of this series coincided with the 9/11 attacks and took on much of its meaning because of this.

William Basinski performing at Chiesa di Santa Maria Annunciata in Chiesa Rossa, Milan, 2017

Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani

On May 17, 2017 Basinski played an hour-long ambient music set inside Dan Flavin’s installation at Chiesa Rossa in Milan, Italy. His performance was divided into three movements, each of which featuring the repetition of a single short audio snippet, and challenged the audience’s endurance in listening to the same sounds repeated over and over, with little variation over time. While this experience is very close to sound art, and the performance was set inside a contemporary art installation, it doesn’t fully constitute sound art since it does not subvert the traditional notions of music performance, nor does it change the nature of the environment in which it is played. Although he isn’t a sound artist, Basinski’s output is closely related to minimalist artwork, and the venues his music has been performed at shows just how close a musician can come to to the contemporary art world.

Although experimental music and sound art often influence each other, and the languages used by their respective artists are sometimes very similar, it’s the intention behind the act that differentiates the two disciplines. While experimental music still aims to shock the listener, in a similar way to how contemporary art aims to shock the viewer, the most relevant aspects in discerning sound art from music are the performative and environmental ones. Sound art, both performed live or reproducing recorded material, is primarily concerned with the composer/performer/listener dichotomy first subverted by John Cage’s 4’ 33”. When the performative aspect doesn’t play a relevant role, it’s the environmental one that makes a difference – sound art is often created or experienced in relation to its venue, and while music can still be inspired by or even sample the sounds of a certain place, it is hardly ever made specifically for a given environment.

Excerpted from Listen Now: The Strategies and Practices of Sound Art.

Contemporary Art and Social Media

February 2017 • File under: Contemporary Art

Nowadays art can be with us at any time and in any place, offering fresh perspectives, raising new questions and adding a spark of curiosity to our daily routines. Through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Pinterest, an increasing number of people can enjoy art and find out about exhibitions happening all around the world. Recent surveys show that an ever-growing percentage of the general public discovers art primarily through social media, rather than by visiting museums and galleries, especially amongst younger demographics. But how is social media influencing the contemporary art world, and which art forms are artists shaping to interpret contemporary cultural and social trends?

Instagram is arguably the most important social network for contemporary art today, and it stands out as a key case-study to understand the digital wave that is shaking the art world. Launched in 2010, the image-sharing platform now counts over 600 million active users. As recent studies have shown, Instagram’s incredible success is due to people’s need for “interaction, archiving, self-expression, escapism and peeking”, – this makes it clear why the visually-driven platform seems to be art enthusiasts’ favourite place to share artworks, and it is also becoming a legitimate contemporary art medium of its own.

Contemporary artists who are using social media in their work

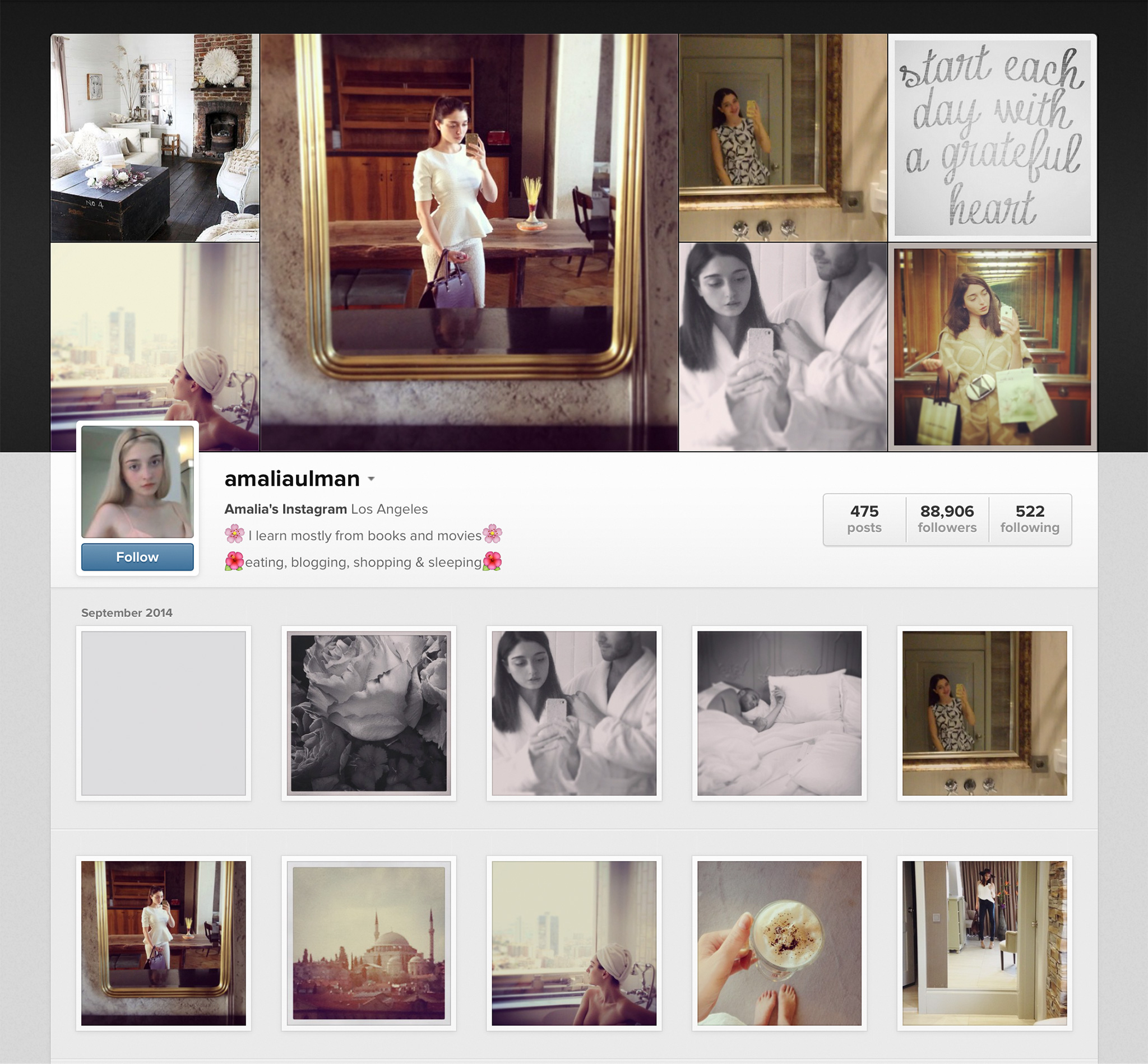

In 2014 Argentinian-born artist Amalia Ulman used her Instagram account (@amaliaulman) as the backdrop for a new kind of performance art, in which she underwent an extreme, semi-fictionalised makeover. Mimicking the poses, lifestyle and aesthetics of the photo sharing platform’s infamous “hot babe”, Ulman conceived her Excellences & Perfections performance as a “boycott” of her own online persona. Last year Tate Modern included Ulman’s work in the exhibition Performing for the Camera, which examined the relationship between photography and performance. This controversial curatorial choice stirred up a discussion about the place of social media art in galleries and museums. As a nascent art vehicle, social-media-based art still has a long way to go before the establishment recognises its value, but it has potential to make art more accessible to a new generation of buyers.

Screenshot of Amalia Ulman’s Instagram project Excellences & Perfections as preserved by Rhizome, a nonprofit organization affiliated with the New Museum. You can view the archived profile here.

Screenshot of Amalia Ulman’s Instagram project Excellences & Perfections as preserved by Rhizome, a nonprofit organization affiliated with the New Museum. You can view the archived profile here.Just days after Amalia Ulman ended her three-month-long Instagram performance in late 2014, Gagosian Gallery presented an exhibition of American artist Richard Prince’s new work. The show, entitled New Portraits, consisted of thirty-seven Instagram screenshots featuring Prince’s own candid, sleazy and somewhat offensive comments, which were blown up and printed on canvas. The work was criticised for showing (and subsequently selling) images that Prince reproduced without the creators’ consent. Controversy and appropriation have always been Prince’s game, but he had never directly engaged the images’ subjects. By reproducing and communicating with Instagram posts and their subjects, Prince’s New Portraits establish a more intimate take on the kind of work that he’s known for.

Challenging the boundaries of the digital realm, Italian artist Marco Strappato has developed a multidisciplinary practice that uses the endless flux of images circulating through social media. In his sculptural work Untitled (Atmosphere/Chemistry/Ozone/Yearly concentration + Ocean/Chemistry/Dissolved Oxygen/5000 meters/Seasonal percentage), 2015, Strappato has manipulated and reframed images from the web, in order to readjust our perception of two-dimensionality and question the construction of images and how our society relates to the media. By investigating emotional and psychological responses of viewers to the images, the artist invites us to critically reassess the common understanding of image production and image distribution.

Marco Strappato, Untitled (Atmosphere/Chemistry/Ozone/Yearly concentration + Ocean/Chemistry/Dissolved Oxygen/5000 meters/Seasonal percentage), 2015. Courtesy the artist.

The role of social media in contemporary art collecting

Furthermore, while artists are commenting on contemporary culture through its own resourceful means of expression, a concurrent shift from physical to digital venues is taking place for artist discovery. Therefore, Instagram and other social networks are also changing the way collectors buy artworks, as online purchases account for an increasing amount of transactions. And since a large portion of the market now lives online, it’s increasingly important for contemporary art galleries to successfully engage with collectors through digital means. On top of being a great way for artists, institutions and galleries to improve outreach and audience engagement, the effective use of social media is becoming an invaluable marketing tool to engage with new audiences and create new sales channels.

While many museums and galleries are steadily increasing their social media presence and contemporary artists are starting to work with and within social networks, there still has not been truly disruptive change in the industry. Instagram has recently introduced ‘shoppable tags’, a non-invasive way for brands to sell their products directly through the app. Although in-person conversations and relationships are a key part of selling art, if galleries are able to communicate more effectively through social media and ordering art through online marketplaces proves itself better than email exchanges, the number of purely digital sales of art are bound to grow. One-tap purchases on Instagram might not be a viable way for galleries to sell artworks, but similar processes are already changing consumer behaviour across every industry.

As contemporary art galleries struggle to keep their brick-and-mortar locations afloat, the growing usage of social media and online marketplaces could allow for online art sales to become a sustainable business model in support of galleries’ traditional operations. In the same way that contemporary artists are making use of social media, either to showcase their work and process, or to host new forms of art, galleries can utilise similar sets of strategies to increment their audience and support artists. Finally, as more artists further develop social media art, perhaps the social media accounts of galleries and museums will become new venues for contemporary artists.

Originally published by Artvisor.